[This commentary was published by the Milbank Quarterly on June 24, 2020.]

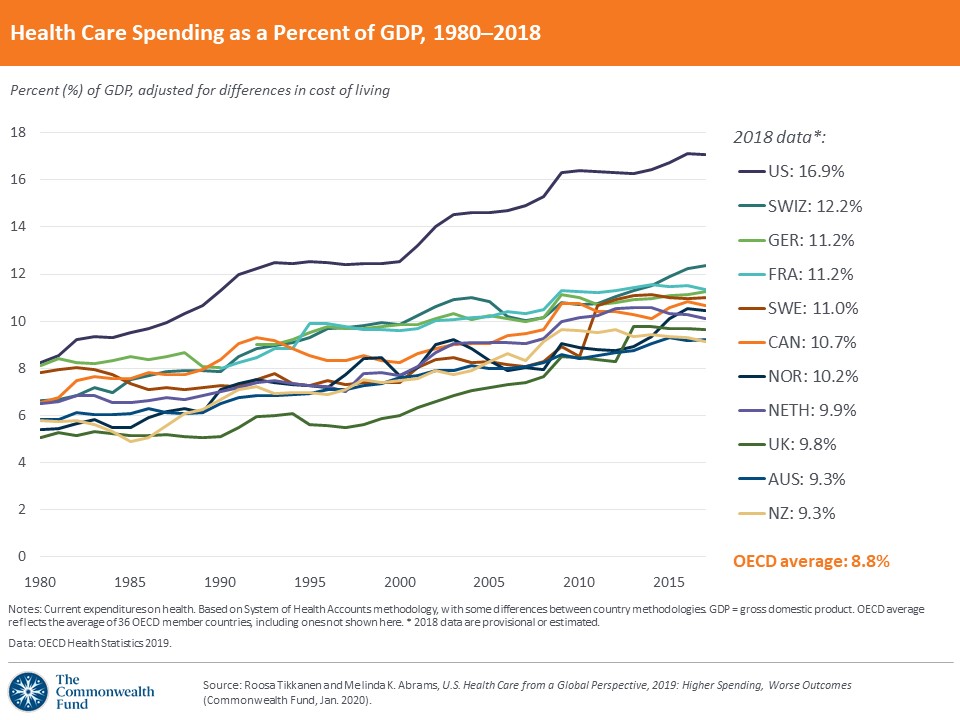

For some years I’ve pondered a Commonwealth Fund chart showing the growth in gross domestic product (GDP) for health care comparing the United States with 10 other high income nations, starting in 1980 and ending in 2018. It shows that 40 years ago, US spending was among the highest but still part of the pack of 11. In the early 1980s, for the first time, US spending leapt above the others, with the distance between the United States and the rest growing ever wider over four decades. This prompts a question: what happened to US health care in the early 1980s–and since then?

Expert opinions abound, as Austin Frakt showed in two New York Times columns on that question, here and here. I suggested then—and now—that a big part of the answer involves the broad economic and political trade winds of the late 1970s and 1980s, often called “Reaganomics” or “supply-side economics” because President Ronald Reagan ushered in a new era in the United States. The term that fits best is “neoliberalism,” which evokes an updating of Adam Smith’s 18th century economic ideas. The 20th century version was inspired by Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek and his key American collaborator, Milton Friedman, among many others. A big part of what happened to US health care in the 1980s and beyond, I hypothesize, for better and worse, resides therein.

Between the late 1940s and the late 1970s, Hayek, Friedman, and collaborators promoted far-reaching ideas to replace the prevailing paradigm of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal liberalism inspired by Keynesian pro-government economics. The neoliberal agenda proposed government reforms in order to guarantee wide-open markets: cutting taxes at all government levels as often as possible, repealing regulations anywhere and everywhere, shrinking or privatizing government at nearly all levels, suppressing organized labor, encouraging free-market trade globally, accepting inequality as the price societies pay for economic freedom, making recipients of publicly provided services and benefits pay as much as possible, and reorienting corporate thinking and behavior to promote return on equity to shareholders as their only legitimate goal. Though health care was not an explicit part of the neoliberal formula, it remained close to Friedman’s thinking (his doctoral dissertation was a frontal assault on government licensure of physicians).

Hayek, Friedman, and company succeeded. Their beliefs became the accepted wisdom of governments across the globe, especially in 1979-1981 with the rise to power of Margaret Thatcher in Great Britain, Deng Xiaoping in China, and Ronald Reagan in the United State, all avid promoters of neoliberal ideas. In prior years, neoliberal ideas (under varied names) had gained prominence in the academy, within corporations and pro-business organizations, and among large numbers of Americans through, for example, the 1980 PBS documentary series, Free to Choose, created and narrated by Friedman with his wife Rose.

The New Deal era lasted for 48 years, from 1933 until Reagan’s inauguration in 1981. The neoliberal era is now in its 40th year. Like any 40 year-old Oldsmobile, rust, cracks, and failing systems abound. Signs include: President Trump’s heretical war on trade, deficit-exploding tax cuts benefiting the wealthy and corporations, anger over “deaths of despair” tied to opioid and other addictions and economic distress, awareness and revulsion about rising levels of inequality across society, and spreading rejection of absolutist “shareholder capitalism.” Last August, the Business Roundtable reversed its 20-year old statement on the “Purpose of the Corporation” to abandon shareholder primacy as the only legitimate goal for corporate America.

But what about health care? Between 1980 and 2020, US health care spending rose far above US economic growth and spending levels in all other high-income nations, while growth in health insurance premiums and cost-sharing increased well beyond advances in household income. On key population health indicators, the United States performs worse than most nations (in some cases, the worst) on life expectancy, infant and maternal mortality, chronic disease mortality (e.g., diabetes), levels of overweight and obesity, suicides, and gun violence), and glaring systemic health inequities. Despite high spending and technological advances, Americans give their system among the lowest satisfaction ratings of any nation. Now with the still-unfolding adverse impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the US health care system stands on a brink. Not a pretty 40-year track record, in spite of oversized capital investments and world-class salaries and profits.

Between 1965 and the 1980s, for the first time, we saw major infusions of investor capital into all corners of our health care system, courtesy of shareholder-owned for-profit companies who often cut long-lasting ties with local communities. Many welcomed this trend as the “right” medicine for what was recognized as an ailing system. In 1984, health care futurist Jeff Goldsmith described the unfolding transition from government controls to deregulated competitive markets as “the death of a paradigm.” Private markets had evolved to a stage, he argued, where they could better control rising health care costs than could government bureaucrats.

In 1986, the Institute of Medicine released a 600-page report on “For Profit Enterprise in Health Care.” Though the Commission documented extraordinary growth in for-profit enterprise across the system in 1965-1985 (with wide sector variations), they found no evidence to convict for-profits of “killing” health care, instead identifying pluses and minuses that called for closer monitoring.

Today, residents of the United States experience higher spending with worse outcomes and the lowest rate of health insurance coverage among high-income nations, even with gains from the Affordable Care Act. And the for-profit acceleration is not slowing. In fact, one of the fastest growing elements in the for-profit space is private equity, often described as “capitalism on steroids.” Most Americans don’t know it, but private equity firms are principally responsible for today’s scandal of “surprise medical billing.”

US health care tends to look inwards to find solutions to big problems within its own tight borders. Yet, looking outside the health care neighborhood may provide compelling insights and important answers.

Outside the health care circle, large segments of the American public want meaningful systemic change. A 2018 document from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Beyond Neoliberalism is a clarion call for a new policy sphere that is forming in think tanks, academia, advocacy and activist organizations, and the legal community, including surprising allies from Republican/conservative quarters, such as Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL), who now publicly rejects the notion of shareholder primacy. The search is on for a new paradigm for American society. Depending on the outcomes of the November 3rd federal elections, this movement may find itself on a fast track to influence or a slow boat to who-knows-where.

Sometimes we’re like fish in a water-filled tank. Noticing the water can be tough because it’s everywhere. While other societies around the globe have vigorous debate over neoliberal policies in their midst, Americans are mostly unaware. To many, the notion that we still live in the Ronald Reagan era seems bizarre. And yet, here we are. As Maya Angelou wrote: “If you don’t know where you’ve come from, you don’t know where you’re going.” Victor Fuchs put it this way in his 2002 book, Who Shall Live?: “If change is to be for the better, it should be based on an understanding of why things are the way they are.”

US health care faces many challenges within its own space. Some of the biggest challenges, though, connect health care to larger American societal concerns, such as inequality and climate change. We’re all in this mess together, and we need to think and act that way more.

Source: Author’s analysis.

Source: Author’s analysis. Source: Author’s analysis. * In 2001, Republicans had Trifecta control until Vermont Senator James Jeffords switched to Democrat in late May of that year.

Source: Author’s analysis. * In 2001, Republicans had Trifecta control until Vermont Senator James Jeffords switched to Democrat in late May of that year.  Source: Author’s analysis.

Source: Author’s analysis.