I haven’t had as much time to write as I would like because of other commitments. One of those commitments has been working on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health program as it relates to the U.S. business community. That experience has deepened my interest in the corporate role in the health care space and the health care role in the business space. This new Milbank commentary outlines some of my interests. More to come, I hope. Please send your comments to: jmcdonough@hsph.harvard.edu

August 19, 2019 was a big day for The Business Roundtable (TBR), the Washington, DC non-profit association of chief executive officers of major US companies. The organization released a new “Statement on the Purpose of the Corporation” signed by 183 CEOs declaring that the interests of workers, customers, communities, and “other stakeholders” should be as important as the interests of a company’s shareholders.1 This represented a significant change from its 1997 Statement that declared “the principal object of a business is to generate economic returns to its owners.”

While actions, not statements, will reveal real intent over time, this change was noteworthy—including for the US health care sector. The subject has deep roots in American society, especially in the advocacy of the late economist Milton Friedman, who derided corporate social responsibility as “fundamentally subversive” and asserted that “there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.”2

In the 1970s and 1980s, Friedman’s notion powered a movement in the United States, Great Britain, and around the globe called “neoliberalism” that promoted deregulation, defanged labor unions, shrunken government, and ever lower taxes. From business schools to high cathedrals of capitalism “greed is good” became more than a movie line from Wall Street and its iconic Gordon Gekko. Binyamin Applebaum’s new book, The Economists’ Hour, lays out the neoliberal narrative, warts and all, in compelling detail.

In recent years, polite rebellion has broken out in business circles against the presumption of shareholder primacy. In January 2019, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, in an open letter to CEOs, asserted that companies that “fulfill their purpose and responsibilities to stakeholders reap rewards over the long term. Companies that ignore them stumble and fall.”3 Back in 2009, then-Microsoft CEO Bill Gates advocated for “creative capitalism” to confront societal needs, while business strategy guru Michael Porter introduced “shared value” into the business lexicon. Whole Foods CEO John Mackey has made hay with his attempted movement and 2013 book Conscious Capitalism.

Today, companies have many organizations, associations, and pathways with which to engage in societal improvement and stakeholder engagement. Environmental, social, and governance criteria (ESG) are the recognized set of standards by which companies are measured for social consciousness, among others.

What about US health care and this neoliberal era in which we still breathe? The connections are multiple, deep, and noteworthy. For starters, of the 183 CEO signers of the TBR statement, only 11 come from companies primarily embedded in the health sector, such as Pfizer, CVS Health, and Siemens, far less than a proportionate share of health care’s 18% jumbo slice of the US economy. And it is not difficult to view TBR’s statement as whitewash, especially when signers include CEOs of Johnson & Johnson and Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, companies that are neck deep in the nation’s opioid marketing scandal.

Influential US political and economic historians refer to the period from the late 1970s through today as the “Reagan era,” crowned during the presidency of Ronald Reagan who declared in his inaugural address that “(i)n this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.” His term in office ushered in the modern era of tax cuts, growing inequality, wage stagnation, diminished unionization, and repeated assaults on government legitimacy. The “Neoliberal Era” may be a better fit. An important question is whether Donald Trump represents the end of this era or the start of something new.

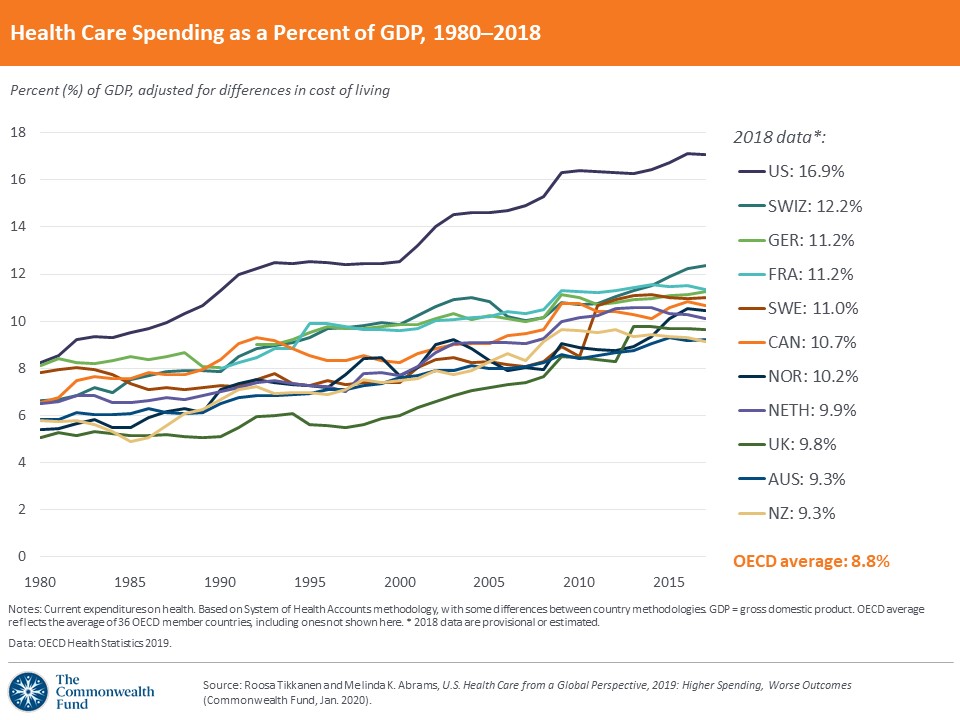

Coincidentally or not, in the early 1980s US national health spending as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) split from rates in other advanced nations toward its current extreme outlier status. US spending on health increased from about 8% of GDP in the late 1970s to 17.8% in 2017, far ahead of the nation with the second highest rate of national spending on health, Switzerland, at 12.2%.

In return for this massive societal investment in medical care, we have the world’s most technologically advanced health care system along with the highest prices in the world for any category of medical services or products one can imagine. The rush of private investment capital into our medical sector has resulted in cutting-edge medical care, advanced drugs and medical devices, and the highest salaries of any professionals in American society.

In these 40 years, we also have seen three consecutive years of declining life expectancy, a deep anomaly among our international peers, humiliating rates of infant and maternal mortality, shocking levels of gun violence, and extreme incidence of overweight and obesity. As economist John Komlos has documented, during World War II, native born Americans were the tallest among advanced nations, both men and women—we are now among the shortest.4 For good measure, Americans are also among the most dissatisfied with our health care system. For what it is worth, money doesn’t buy us good health or happiness.

In this epoch, we have seen enormous growth in private investor funding into a sector formerly dominated by nonprofits or government, in hospitals, physician practices, home health, hospice, air ambulances, and much more. The pharmaceutical industry has always been for-profit, yet its extraordinary concentration has ballooned its pricing structure. The for-profit health sector keeps evolving, assuming new forms. As Gondi and Song document, between 2010 and 2017 the value of private equity deals involving acquisition of health-related companies, mostly hospitals and physician practices, increased 187% reaching $42.6 billion.5

Could the investor dominance of much of US health care explain at least part of our outlier status on health spending and outcomes? It is hard to imagine that the investor-driven corporatization of American society could have left medical care untouched. Even today, the most common complaint from conservatives and Republicans about US health care is that government regulation thwarts the free market.

The notion that we could put this massive bulk of toothpaste back into the tube seems preposterous. The economic and political power of the incumbent system would easily stymie any serious challenge, including the apparent one, a nationalized “Medicare for All” structure. Assuming anything of this magnitude could get through Congress—or the Supreme Court—is a daunting stretch. And yet, the real frustrations of Americans with a system organized first and foremost to serve money and power before patients deserve attention.

If, as the Business Roundtable advocates, we are embarking on a new national conversation concerning the role of the for-profit corporation in American society, perhaps we should also instigate a parallel and sustained national examination and conversation about the history, experience, and results from for-profit corporatization of our health and medical care sector. It is clear that this revolution produces good and bad results for American society and for the world. Is it time for a reckoning?

References

- The Business Roundtable. Statement on the Purpose of the Corporation. Washington, DC. August 19, 2019. https://opportunity.businessroundtable.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/BRT-Statement-on-the-Purpose-of-a-Corporation-with-Signatures.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- Friedman M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine. September 13, 1970.

- Fink L. Larry Fink’s 2019 letter to CEOs: profit and purpose. BlackRock. January 2019. https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- Komlos J, Buar M. From the tallest to (one of) the fattest: the enigmatic fate of the American population in the 20th century. Economics and Human Biology. 2004;2:57-74.

- Gondi S, Song Z. Potential implications of private equity investments in health care delivery. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1047-1058.

Published in 2019

DOI: 10.1111/1468-0009.12432

Source: Author’s analysis.

Source: Author’s analysis. Source: Author’s analysis. * In 2001, Republicans had Trifecta control until Vermont Senator James Jeffords switched to Democrat in late May of that year.

Source: Author’s analysis. * In 2001, Republicans had Trifecta control until Vermont Senator James Jeffords switched to Democrat in late May of that year.  Source: Author’s analysis.

Source: Author’s analysis.